Earth-Like Planet Found, But What Does It Mean?

By now, most people have heard the news about the discovery by a team of Swiss, French and Portuguese scientists of an earth-like planet just 20.5 light years away from Earth. The news has clearly captured the imagination of scientific writers and people around the world, in no small part because the potential implications of what we might learn about the planet are deep with existential meaning. (This AP title — "Planet-finder says search for alien life next" — exemplifies the anticipatory nature of the coverage.)

But reigning in our imaginations for a moment, what did the scientists truly discover, and how?

Universe Today offers some good detail on the discovery:

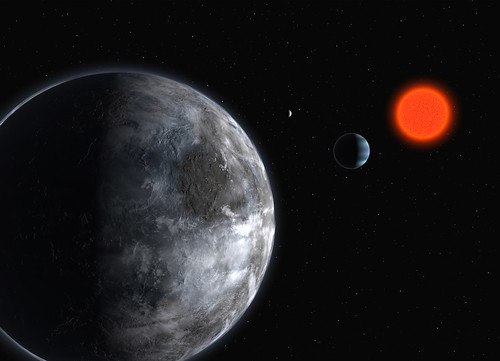

The host star is called Gliese 581, and it’s one of the 100 closest star to us, located only 20.5 light years away in the constellation Libra. Unlike our Sun, it’s a red dwarf star, emitting much less light and energy. This brings its habitable zone in close and tight to the star. For a planet to be orbiting its parent star within this habitable zone, it’s got to have a really tight orbit.

And this is how the planet was discovered. It was made by measuring the star’s radial velocity, where the planet’s gravity tugs its parent star back and forth (aka, the Wobble Method). Astronomers can measure this velocity with tremendous precision to determine the planet’s mass and orbital period. And the tool for the job is the European Southern Observatory’s HARPS (High Accuracy Radial Velocity for Planetary Searcher) spectrograph connected to the 3.6-m telescope at La Silla, Chile.

The planet is “Earth-like”, but it wouldn’t seem much like home. It’s 50% larger than the Earth, and has about 5 times our planet’s mass. It also completes an orbit every 13 days – it’s 14 times closer to its star than the Earth is to the Sun. Since it’s in the habitable zone, there would very likely be liquid water on its surface.

Unfortunately, the radial method only tells astronomers what the planet’s mass and orbital distance are. They’re not directly observing it. So there’s no way to know if there is actually water on the surface, or even oxygen in the atmosphere that would indicate the presence of life. But future missions, like Darwin, will certainly put it in the cross hairs to get a better look for life.

The discovery was made by a team of astronomers at the European Southern Observatory in Chile. Naturally they are the go-to source for additional information, including this summary video already up on YouTube.

The press release from ESO also tells us that computer models indicate that the planet should be "either rocky — like our Earth — or fully covered with oceans."

The ESA’s Darwin Flotilla (artist’s rendering below; scheduled for launch in 2015) will give scientists additional tools in exploring Gliese 581 and other exoplanets that may harbor life.

And perhaps this discovery will jump start a new, friendly "space race" to discover details about distant exoplanets. As The daily Tribune de Geneve boastfully pointed out, "American scientists recently estimated that the discovery of an exoplanet resembling the Earth would probably take 20 years," it wrote. "The Europeans didn’t wait for them."