Satcom Smartphone

In the Northeast U.S., there aren’t many places your mobile phone doesn’t get a signal. Sure, there are little pockets where you don’t, and in remote areas it can get a little tricky. In those instances, it sure would be nice to have a system available like Thuraya — a hybrid satellite/GSM network.

Most of the time, you’re using the GSM portion of your mobile. Out in the desert — lots of that type of terrain in the Middle East — your mobile connects via a specialized geosynchronous satellite. Apparently, it works well enough so you don’t notice, but you probably get used to the inherent latency (your signal has a 45,000 mile round trip to complete, so at the speed of light figure at least a quarter-second of delay).

In the fully developed world, satellite phones have yet to be financially successful. Through bankruptcy, Iridium and Globalstar have been able to survive. Iridium was almost shut down completely were it not for the U.S. Department of Defense — they saw the value of a unique, diverse path for voice and narrow-band communications, so they kept it afloat.

Last week, TerreStar got some ink in USA Today:

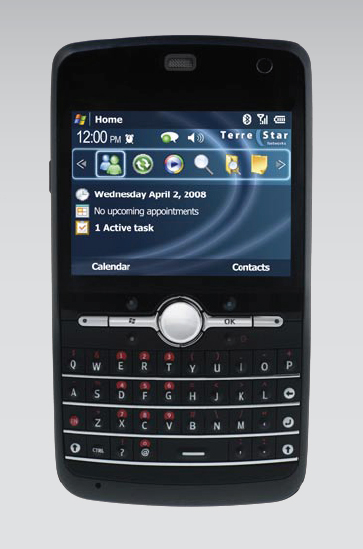

The first handsets for TerreStar’s satellite would cost about $700, said TerreStar chief executive Jeff Epstein. At a cellphone trade show here last week, the company displayed a prototype built by small Finnish company, Elektrobit. The phone has a QWERTY keyboard and runs Windows Mobile software, making it similar to many BlackBerry-style, e-mail-oriented phones for corporate use, but a bit thicker. Unlike Iridium and Globalstar phones, there’s no protruding antenna.

"This way, you take your BlackBerry and you replace it with that device," Epstein said.

Both companies indicate that calling over a satellite will cost less than $1 per minute, the approximate price of Iridium calls. TerreStar also has a roaming agreement with AT&T Inc. for calls that don’t go through the satellite, and expects the combined satellite and ground system to be working before the end of this year.

However, neither TerreStar or SkyTerra will replicate Iridium’s worldwide coverage. The phones will work in North America only. Nor will they be getting away from a significant limitation of satellite phones: The handsets need to be in clear view of a satellite. In other words, the satellite service will work only outdoors, and a hill, tree or building obscuring the southern sky can be a problem, especially if you’re far north.

Given these limitations, and the steady expansion of ground-based networks, is there really a mass demand for satellite phones?

Satellite analyst and consultant Tim Farrar at TMF Associates is skeptical. He believes the number of people interested in satellite calling, even if just for emergencies, is small compared to the overall cellphone market.

"They need hundreds of thousands and more likely millions of users of these handsets to make it into the mainstream," he said. "You have to gain an awful lot of momentum before manufacturers will consider it worthwhile to build this into their handsets."

Farrar thinks marketing will be a challenge too. For mainstream adoption, sales representatives at cellphone stores would have to get customers to accept that the satellite connectivity would work only outdoors.

"Last time around, people tried out Iridium phones, and thought ‘What use is this to me if I have to go out and stand in the middle of a field to make a call?"’ he said.

Given these obstacles, Farrar believes the value of SkyTerra and TerreStar is in their spectrum holdings. The companies have permission from the Federal Communications Commission to use slices of the airwaves for both satellite and ground-based networks, as long as they have a satellite in orbit. The government hoped that such hybrid space-terrestrial licenses would encourage companies to provide emergency satellite coverage when cell towers are knocked out by disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

For now SkyTerra and TerreStar aren’t using their spectrum for ground-based communications. Eventually, the companies could try to put the airwaves to use with their own cell towers on the ground — or they could use that spectrum to entice a carrier like AT&T or Verizon Wireless. Those companies would normally have to pay billions for spectrum with nationwide coverage, but they might find that snapping up one of these satellite companies is a cheaper way to get that access, said Armand Musey, a satellite consultant.

Investors aren’t optimistic: Terrestar, which is listed on the Nasdaq, has a market capitalization of $72 million, which is paltry compared to the cost of its satellite system. SkyTerra is privately held.

"There certainly is not a market for having all of these companies — TerreStar, SkyTerra, Inmarsat, Iridium — all operating satellite-only," Musey said. "The market is just not that big."

The news from Elektrobit of Finland will be manufacturing the handset is about a year old, but this isn’t the first time satcom news gets recycled (case in point: Americom’s DigitalC in 1999 and again in 2000).

The TerreStar-1 satellite is scheduled to launch in June, 2009, via an Ariane 5 launch vehicle. Space Systems/Loral has been building it since 2005.

Let’s hope a smart business follows.