Shake, Shake, Shake

Mobile Satellite Ventures is proposing a system to help predict earthquakes in the U.S. Naturally, it’s a satellite-based system:

Mobile Satellite Ventures (MSV) today announced that it has joined with the Central United States Earthquake Consortium (CUSEC) to form a new satellite mutual aid radio talkgroup (SMART) dedicated to the preparation for and response to earthquakes throughout the central United States.

CUSEC is a partnership of the federal government and eight states most affected by earthquakes in the central U.S. including Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. The organization serves as the coordinating hub for the multi-state region and as a partnership of organizations to mediate disasters and save lives caused by earthquakes in the central U.S.

MSV is expected to shake things up with their new satellite, MSV-1, expected to launch in 2009 and based on Boeing’s GeoMobile platform (like Thuraya, but bigger). Wait a minute: where’s California? They have their own earthquake people. But central U.S.? There was an earthquake measuring 5.2 on the Richter Scale in the Wabash Valley on 18 April 2008, via The Southern Illinoisan:

An earthquake centered in southern Illinois rocked people awake across the Midwest early Friday, surprising residents unaccustomed to such seismic activity.

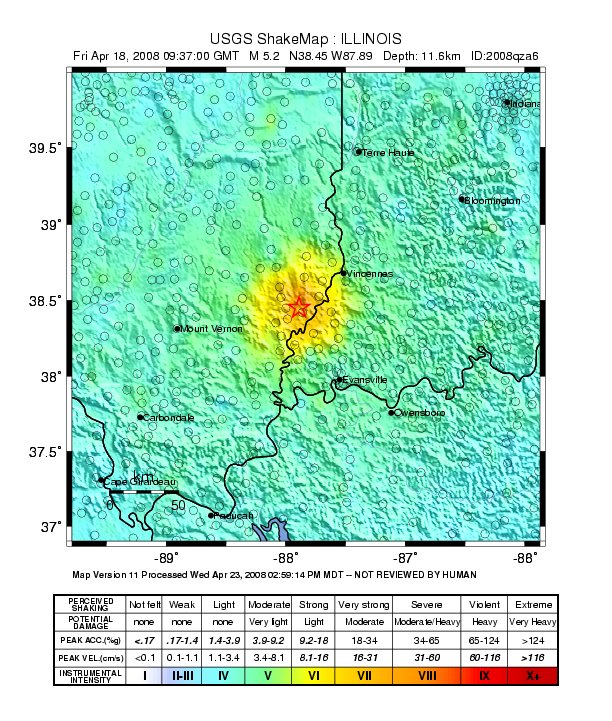

The quake just before 4:37 a.m. was centered 6 miles from West Salem, Ill., and 66 miles west of Evansville, Ind.

Initially pegged as a 5.4 earthquake, the U.S. Geological Survey revised its estimate to give it a value of 5.2.

West Salem is in Edwards County, and dispatcher Lucas Griswold says the sheriff’s department received several calls about the earthquake but only reports of minor damage and no injuries.

“Oh, yeah, I felt it. It was interesting,” Griswold said. “A lot of shaking.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Australian Broadcasting is reporting a new satellite system for predicting earthquakes using ionospheric dimpling:

The theory suggests that much of earth’s rock has soaked up water, which has later been exposed to extreme heat and pressure inside the earth. Those conditions break apart the water and create the electrically conductive crystals that exist inside most rocks, as well as byproducts such as oxygen.

As pressure builds before an earthquake, the oxygen molecules inside the rocks undergo chemical reactions, creating a positive electrical charge that radiates out toward the earth’s surface.

"It’s similar to how an electrical charge radiates through a battery," says Freund.

The charge creates a subtle fluorescent, infrared glow and a magnetic field one to two weeks before a major earthquake.

That light shines into space, the theory goes, where satellites can register the change.

Low-resolution thermal cameras aboard the proposed satellites would scan the earth to detect earthquake precursors, says Eves.

The positively charged magnet creates a dimple, up to 20 kilometres deep, in the earth’s atmosphere by attracting negatively charged ions from as far away as 600 kilometres above the surface of the Earth.

To detect this ionospheric dimpling, the satellites would monitor the existing Global Positioning Satellite System with three small GPS antennas on its side. As each GPS satellite comes up over the horizon, its signal would pass through the ionosphere. Any dimpling would change that signal.

The theory is not without skeptics.

"As far as I know, there is no published research to suggest that this will work," says Dr Mike Blanpied, who is with the United States Geologic Survey’s Earthquake Hazards Program.

This early-warning system was reported by the Wall Street Journal last month:

Early in May, NASA earth scientists monitoring infrared images of the earth noticed unusual patterns in southwestern China. One sent an email to colleagues, noting: Something is happening in Sichuan province.

For Friedemann Freund, a chemist-turned-NASA geophysics researcher, it was more support for his simple, though hotly contested theory: Earthquakes are the culmination of drawn-out physical processes that can be tracked sometimes more than a week ahead of the main event.

The main idea: Rocks put under enough pressure — for example, when tectonic plates shift — turn into batteries. The resulting electrical currents can travel miles into the earth, Dr. Freund says. The infrared images observed by NASA, for example, were concentrated several hundred miles from the epicenter of the roughly 8.0 magnitude earthquake that struck on May 12, killing at least 34,000 people.Dr. Freund describes his discovery as simple, made at 2 p.m. on a Friday afternoon in early 2005 just before he and his graduate students finished packing up a temporary laboratory they had been using. For experiment No. 167, one for the road, they decided to use a copper contact to test whether a squeezed rock emitted a current. It did.

"This is something that should have been discovered 50 years ago," he said.

Certainly, people have tried. For more than a century, researchers have debated the pursuit of the "holy grail" of earthquake prediction. There is still no widespread support for linking electromagnetic signals, infrared emissions or atmospheric changes to an approaching quake.

Satellites are used to communicate seismic data, and transmitting videos, of course. The prospect of being able to predict such events many days in advance seems like a real possibility. Count on the Smithsonian to present it, probably based on a published piece by Dr. Ouzounov of George Mason University.