Now that we have the two satellite radio companies combined, are we that far off from the two major satellite TV companies trying to merge again? Good question.

Dish-DirecTV Deal Won’t Fool Feds

Prompted by the first subscriber losses at a major U.S. satellite-TV provider, Dish NetworkDISH could revive a merger attempt with rival DirecTVDTV, but industry observers say a potential deal will once again be found to be anticompetitive.

Six years removed from failing at a $16 billion tie-up, Dish Network Chairman and CEO Charles Ergen has said market conditions are more welcoming to a deal, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal. Ergen has reportedly calculated the potential savings of a merger at up to $2 billion a year, and he also harbors hopes of a potent broadband offering from a combined satellite company — something neither has been done individually.

However, a renewed bid to combine Dish and DirecTV would revisit the same problems that plagued the 2002 attempt — and would once again fail to pass muster with the Federal Communications Commission and the Justice Department, the government bodies that would again examine the merger.

In its October 2002 decision, the FCC said a combination of Dish Network, then under the umbrella of parent EchoStarSATS, and DirecTV, which was then owned by Hughes Electronics, would likely harm consumers by eliminating a viable competitor in every market, creating the potential for higher prices and lower service quality, and hurting future innovation.

Three weeks later, the Justice Department agreed that a merger would reduce competition in markets served by cable, and eliminate it in areas served only by direct broadcast satellite.

"That merger was the first in recent memory that the FCC turned down," says Adam Candeub, an associate assistant professor of law at Michigan State University College of Law, who was an attorney-adviser for the FCC and worked on the 2002 deal between Dish and DirecTV. "That’s something [Dish and DirecTV] would like to correct and would give it another go-round."

The recently approved deal between Sirius Satellite RadioSIRI and XM Satellite Radio has given Dish’s Ergen hope, though, that consolidation among satellite companies would be better received by government officials, especially if both Dish and DirecTV can argue they compete not only against each other but cable and telecom companies, such as ComcastCMCSA, AT&TT and VerizonVZ, which have started bundling television, Internet, and phone services.

However, when going strictly by FCC and Justice comments about both Dish and DirecTV – and about XM and Sirius — Candeub argues that the government bodies would not likely bend to concessions, even if Ergen wants to use the XM-Sirius deal as a blueprint.

"From a market-definition perspective, it’s not clear that the satellite radio market has much to do with the video market," Candeub says. "They’re very different. There are so many various ways to get audio, like AppleAAPL iPods. Arguably, one analysis would not work for the other."

The Journal reported that Ergen, attempting to assuage fears over what a Dish-DirecTV merger would do to the competitive landscape, is willing to peg monthly charges to the lowest fees paid by subscribers in rural regions, where satellite antennas are currently the only way for customers to receive pay-TV options. A cap on prices would be similar to Sirius and XM’s pledge to hold off on price increases for three years after their merger was completed.

Craig Moffett, senior analyst for U.S. cable and satellite broadcasting with Sanford Bernstein, says that a commitment to national pricing is one way to ameliorate the potential for monopoly pricing power in rural markets, although such a move would still not prevent a deal from being labeled anticompetitive.

"These kinds of concessions are commonplace in the FCC … but the test in the [Justice Department] is an objective ‘rule of law’ test," he writes in a research note. "Voluntary a priori commitments such as national pricing plans are therefore generally not considered as relevant when considering whether a merger does or doesn’t meet the letter of the law."

Moffett adds that under the precedent set by Sirius and XM, the two satellite-TV providers would have to prove there was an alternative distribution model for television in rural areas, one that would be a suitable substitute for Dish and DirecTV’s service. One approach would be to wait until TV-over-the-Internet connections are more available to rural customers, although Moffett finds that to be a Catch-22.

"This itself is problematic, inasmuch as TV-over-the-Internet requires a high quality broadband connection, which generally means either cable modem or telco fiber," Moffett says. "The very definition of ‘rural’ to be applied by the [Justice Department] in 2002 presumes that connections of this kind are not available."

Of course, a few variables have changed that arguably could make a deal more palatable for regulators. "When the Dish/DirecTV merger was out there in 2002, there was a Republican majority in the Senate," Candeub says. "Many of those Senate seats were held by Republicans who represent people from big rural states who rely on satellite and who would see higher rates."

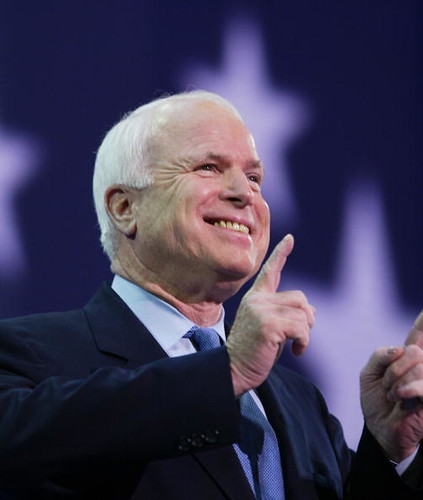

In the last six years, though, there has been a shift of political power. While then-FCC Chairman Michael Powell, a Republican, argued that a Dish and DirecTV combination would replace competition with "a regulated monopoly," a Democratic majority in Washington might be more open to regulation of satellite television.

Despite this shift, though, analysts say those pesky laws cannot simply be circumnavigated. "In rural America, a merger would still be two [companies in the field]-to-one. Two-to-one mergers are unlawful under U.S. antitrust law," Moffett asserts. "Nothing in six years has changed."

Hey, you never know.

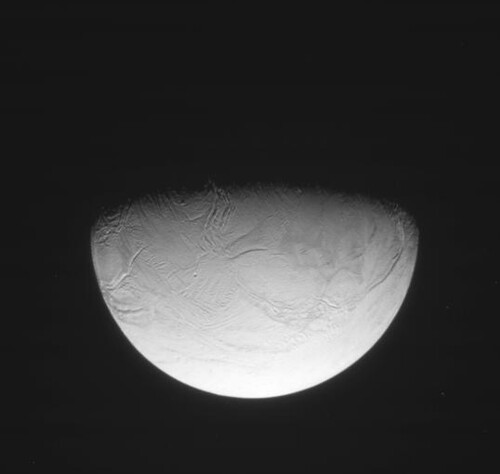

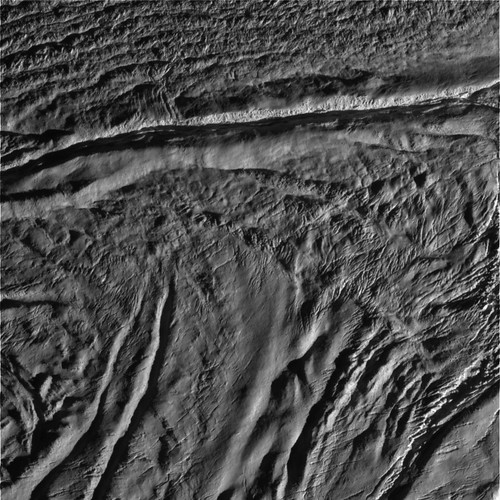

This Thursday, August 14, 2008, an Ariane 5 rocket is scheduled to lift the

This Thursday, August 14, 2008, an Ariane 5 rocket is scheduled to lift the