I remember watching the first human steps on the Moon on 20 July 1969, along with a couple of hundred people at a hotel in the Catskills. It was the only TV set around.

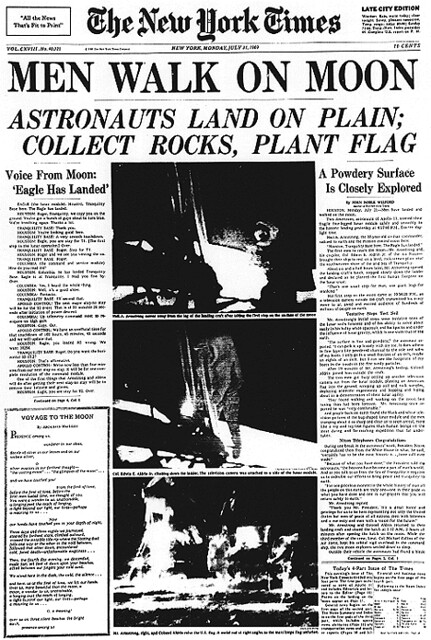

Men have landed and walked on the moon.

Two Americans, astronauts of Apollo 11, steered their fragile four-legged lunar module safely and smoothly to the historic landing yesterday at 4:17:40 P.M., Eastern daylight time.

Neil A. Armstrong, the 38-year-old civilian commander, radioed to earth and the mission control room here:

“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

The first men to reach the moon–Mr. Armstrong and his co-pilot, Col. Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. of the Air Force–brought their ship to rest on a level, rock-strewn plain near the southwestern shore of the arid Sea of Tranquility.

About six and a half hours later, Mr. Armstrong opened the landing craft’s hatch, stepped slowly down the ladder and declared as he planted the first human footprint on the lunar crust:

“That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

His first step on the moon came at 10:56:20 P.M., as a television camera outside the craft transmitted his every move to an awed and excited audience of hundreds of millions of people on earth.

Tentative Steps Test Soil

Mr. Armstrong’s initial steps were tentative tests of the lunar soil’s firmness and of his ability to move about easily in his bulky white spacesuit and backpacks and under the influence of lunar gravity, which is one-sixth that of the earth.

“The surface is fine and powdery,” the astronaut reported. “I can pick it up loosely with my toe. It does adhere in fine layers like powdered charcoal to the sole and sides of my boots. I only go in a small fraction of an inch, maybe an eighth of an inch. But I can see the footprints of my boots in the treads in the fine sandy particles.

After 19 minutes of Mr. Armstrong’s testing, Colonel Aldrin joined him outside the craft.

The two men got busy setting up another television camera out from the lunar module, planting an American flag into the ground, scooping up soil and rock samples, deploying scientific experiments and hopping and loping about in a demonstration of their lunar agility.

They found walking and working on the moon less taxing than had been forecast. Mr. Armstrong once reported he was “very comfortable.”

And people back on earth found the black-and-white television pictures of the bug- shaped lunar module and the men tramping about it so sharp and clear as to seem unreal, more like a toy and toy-like figures than human beings on the most daring and far- reaching expedition thus far undertaken.

Nixon Telephones Congratulations

During one break in the astronauts’ work, President Nixon congratulated them from the White House in what, he said, “certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made.”

“Because of what you have done,” the President told the astronauts, “the heavens have become a part of man’s world. And as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility it required us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to earth.

“For one priceless moment in the whole history of man all the people on this earth are truly one–one in their pride in what you have done and one in our prayers that you will return safely to earth.”

Mr. Armstrong replied:

“Thank you Mr. President. It’s a great honor and privilege for us to be here representing not only the United States but men of peace of all nations, men with interests and a curiosity and men with a vision for the future.”

Mr. Armstrong and Colonel Aldrin returned to their landing craft and closed the hatch at 1:12 A.M., 2 hours 21 minutes after opening the hatch on the moon. While the third member of the crew, Lieut. Col. Michael Collins of the Air Force, kept his orbital vigil overhead in the command ship, the two moon explorers settled down to sleep.

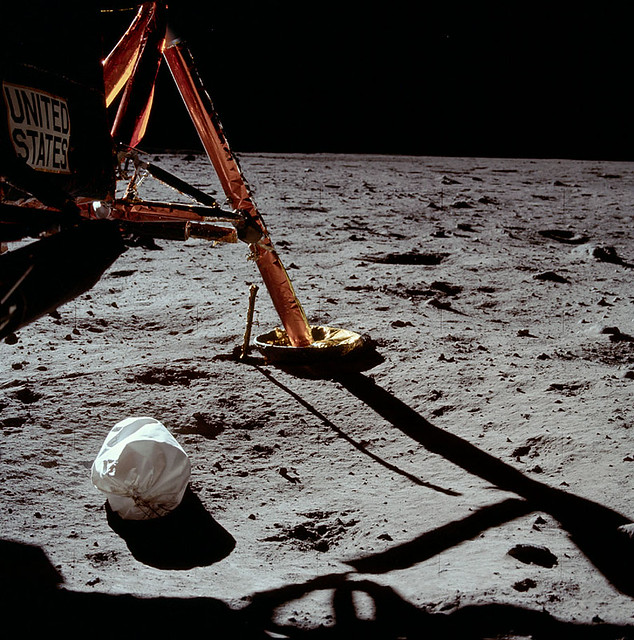

Outside their vehicle the astronauts had found a bleak world. It was just before dawn, with the sun low over the eastern horizon behind them and the chill of the long lunar nights still clinging to the boulders, small craters and hills before them.

Colonel Aldrin said that he could see “literally thousands of small craters” and a low hill out in the distance. But most of all he was impressed initially by the “variety of shapes, angularities, granularities” of the rocks and soil where the landing craft, code-named Eagle had set down.

The landing was made four miles west of the aiming point, but well within the designated area. An apparent error in some data fed into the craft’s guidance computer from the earth was said to have accounted for the discrepancy.

Suddenly the astronauts were startled to see that the computer was guiding them toward a possibly disastrous touchdown in a boulder-filled crater about the size of a football field.

Mr. Armstrong grabbed manual control of the vehicle and guided it safely over the crater to a smoother spot, the rocket engine stirring a cloud of moon dust during the final seconds of descent.

Soon after the landing, upon checking and finding the spacecraft in good condition, Mr. Armstrong and Colonel Aldrin made their decision to open the hatch and get out earlier than originally scheduled. The flight plan had called for the moon walk to begin at 2:12 A.M.

Flight controllers here said that the early moon walk would not mean that the astronauts would also leave the moon earlier. The lift-off is scheduled to come at about 1:55 P.M. today.

Their departure from the landing craft out onto the surface was delayed for a time when they had trouble depressurizing the cabin so that they could open the hatch. All the oxygen in the cabin had to be vented.

Once the pressure gauge finally dropped to zero, they opened the hatch and Mr. Armstrong stepped out on the small porch at the top of the nine-step ladder.

“O.K., Houston, I’m on the porch,” he reported, as he descended.

On the second step from the top, he pulled a lanyard that released a fold-down equipment compartment on the side of the lunar module. This deployed the television camera that transmitted the dramatic pictures of man’s first steps on the moon.

Ancient Dream Fulfilled

It was man’s first landing on another world, the realization of centuries of dreams, the fulfillment of a decade of striving, a triumph of modern technology and personal courage, the most dramatic demonstration of what man can do if he applies his mind and resources with single-minded determination.

The moon, long the symbol of the impossible and the inaccessible, was now within man’s reach, the first port of call in this new age of spacefaring.

Immediately after the landing, Dr. Thomas O. Paine, administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, telephoned President Nixon in Washington to report:

“Mr. President, it is my honor on behalf of the entire NASA team to report to you that the Eagle has landed on the Sea of Tranquility and our astronauts are safe and looking forward to starting the exploration of the moon.”

The landing craft from the Apollo 11 spaceship was scheduled to remain on the moon about 22 hours, while Colonel Collins of the Air Force, the third member of the Apollo 11 crew, piloted the command ship, Columbia, in orbit overhead.

“You’re looking good in every respect,” Mission Control told the two men of Eagle after examining data indicating that the module should be able to remain on the moon the full 22 hours.

Mr. Armstrong and Colonel Aldrin planned to sleep after the moon walk and then make their preparations for the lift-off for the return to a rendezvous with Colonel Collins in the command ship.

Apollo 11’s journey into history began last Wednesday from launching pad 39-A at Cape Kennedy, Fla. After an almost flawless three-day flight, the joined command ship and lunar module swept into an orbit of the moon yesterday afternoon.

The three men were awake for their big day at 7 A.M. when their spacecraft emerged from behind the moon on its 10th revolution, moving from east to west across the face of the moon along its equator.

Their orbit was 73.6 miles by 64 miles in altitude, their speed 3,660 miles an hour. At that altitude and speed, it took about two hours to complete a full orbit of the moon.

The sun was rising over their landing site on the Sea of Tranquility.

“We can pick out almost all of the features we’ve identified previously,” Mr. Armstrong reported.

After breakfast, on their 11th revolution Colonel Aldrin and then Mr. Armstrong, both dressed in their white pressurized suits, crawled through the connecting tunnel into the lunar module.

They turned on the electrical power, checked all the switch settings on the cockpit panel and checked communications with the command ship and the ground controllers. Everything was “nominal,” as the spacemen say.

LM Ready for Descent

The lunar module was ready. Its four legs with yard-wide footpads were extended so that the height of the 16-ton vehicle now measured 22 feet and 11 inches and its width 31 feet.

Mr. Armstrong stood at the left side of the cockpit, and Colonel Aldrin at the right. Both were loosely restrained by harnesses. They had closed the hatch to the connecting tunnel.

The walls of their craft were finely milled aluminum foil. If anything happened so that it could not return to the command ship, the lunar module would be too delicate to withstand a plunge through earth’s atmosphere, even if it had the rocket power.

Nearly three-fourths of the vehicle’s weight was in propellants for the descent and ascent rockets–Aerozine 50 and nitrogen oxide, which substituted for the oxygen, making combustion possible.

It was an ungainly craft that creaked and groaned in flight. But years of development and testing had determined that it was the lightest and most practical way to get two men to the moon’s surface.

Before Apollo 11 disappeared behind the moon near the end of its 12th orbit, mission control gave the astronauts their “go” for undocking–the separation of Eagle from Columbia.

Colonel Collins had already released 12 of the latches holding the two ships together at the connecting tunnel. He did this when he closed the hatch at the command ship’s nose. While behind the moon, he was to flip a switch on the control panel to release the three remaining latches by a spring action.

At 1:50 P.M., when communications signals were reacquired, Mission Control asked: “How does it look?”

“Eagle has wings,” Mr. Armstrong replied.

The two ships were then only a few feet apart. But at 2:12 P.M., Colonel Collins fired the command ship’s maneuvering rockets to move about two miles away and in a slightly different orbit from the lunar module.

“It looks like you’ve got a fine-looking flying machine there, Eagle, despite the fact you’re upside down,” Colonel Collins commented, watching the spidery lunar module receding in the distance.

“Somebody’s upside down,” Mr. Armstrong replied.

What is “up” and what is “down” is never quite clear in the absence of landmarks and the sensation of gravity’s pull.

As Mr. Armstrong and Colonel Aldrin rode the lunar module back around to the moon’s far side, the rocket engine in the vehicle’s lower stage was pointed toward the line of flight. The two pilots were leaning toward the cockpit controls, riding backwards and facing downward.

“Everything is ‘go,'” they were assured by Mission Control.

Their on-board guidance and navigation computer was instructed to trigger a 29.8-second firing of the descent rocket, the 9,870-pound-thrust throttable engine that would slow down the lunar module and send it toward the moon on a long, curving trajectory.

The firing was set to take place at 3:08 P.M., when the craft would be behind the moon and once again out of touch with the ground.

Suspense built up in the control room here. Flight controllers stood silently at their consoles. Among those waiting for word of the rocket firing were Dr. Thomas O. Paine, the space agency’s administrator, most of the Apollo project officials and several astronauts.

At 3:46 P.M., contact was established with the command ship.

Colonel Collins reported, “Listen, baby, things are going just swimmingly, just beautiful.”

There was still no word from the lunar module for two minutes. Then came a weak signal, some static and whistling, and finally the calm voice of Mr. Armstrong.

“The burn was on time,” the Apollo 11 commander declared.

When he read out data on the beginning of the descent, Mission Control concluded that it “look great.” The lunar module had already descended from an altitude of 65.5 miles to 21 miles and was coasting steadily downward.

Eugene F. Kranz, the flight director, turned to his associates and said, “We’re off to a good start. Play it cool.”

Colonel Aldrin reported some oscillations in the vehicle’s antenna, but nothing serious. Several times the astronauts were told to turn the vehicle slightly to move the antenna into a better position for communications over the 230,000 miles.

“You’re ‘go’ for PDI,” radioed Mission Control, referring to the powered descent initiation–the beginning of the nearly 13-minute final blast of the rocket to the soft touchdown.

When the two men reached an altitude of 50,000 feet, which was approximately the lowest point reached by Apollo 10 in May, green lights on the computer display keyboard in the cockpit blinked the number 99.

This signaled Mr. Armstrong that he had five seconds to decide whether to go ahead for the landing or continue on its orbital path back to the command ship. He pressed the “proceed” button.

The throttleable engine built up thrust gradually, firing continuously as the lunar module descended along the steadily steepening trajectory to the landing site about 250 miles away:

“Looking good,” Mission Control radioed the men.

Four minutes after the firing the lunar module was down to 40,000 feet. After five and a half minutes, it was 33,500 feet. At six minutes, 27,000 feet.

“Better than the simulator,” said Colonel Aldrin, referring to their practice landings at the spacecraft center.

Seven minutes after the firing, the men were 21,000 feet above the surface and still moving forward toward the landing site. The guidance computer was driving the rocket engine.

The lunar module was slowing down. At an altitude of about 7,200 feet, with the landing site still about five miles ahead, the computer commanded control jets to fire and tilt the bug-shaped craft almost upright so that its triangular windows pointed forward.

Mr. Armstrong and Colonel Aldrin then got their first close-up view of the plain they were aiming for. It was then about three and a half minutes to touchdown.

The brownish-gray panorama rushed below them–myriad craters hills and ridges, deep cracks and ancient rubble on the moon, which Dr. Robert Jastrow, the space agency scientist, called the “Rosetta Stone of life.”

“You’re ‘go’ for landing,” Mission Control informed the two men.

The Eagle closed in, dropping about 20 feet a second, until it was hovering almost directly over the landing area at an altitude of 500 feet.

Its floor was littered with boulders.

It was when the craft reached an altitude of 300 feet that Mr. Armstrong took over semimanual control for the rest of the way. The computer continued to have control of the rocket firing, but the astronaut could adjust the craft’s hovering position.

He was expected to take over such control anyway, but the sight of a crater looming ahead at the touchdown point made it imperative.

As Mr. Armstrong said later, “The auto-targeting was taking us right into a football field- sized crater, with a large number of big boulders and rocks.”

For about 90 seconds, he peered through the window in search of a clear touchdown point. Using the lever at his right hand, he tilted the vehicle forward to redirect the firing of the maneuvering jets and thus shift its hovering position.

Finally, Mr. Armstrong found the spot he liked, and the blue light on the cockpit flashed to indicate that five-foot-long probes, like curb feelers, on three of the four legs had touched the surface.

“Contact light,” Mr. Armstrong radioed.

He pressed a button marked “Stop” and reported, “okay, engine stop.”

There were a few more cryptic messages of functions performed.

Then Maj. Charles M. Duke, the capsule communicator in the control room, radioed to the two astronauts:

“We copy you down, Eagle.”

“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

“Roger, Tranquility,” Major Duke replied. “We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We are breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

Colonel Aldrin assured Mission Control it was a “very smooth touchdown.”

The Eagle came to rest at an angle of only about four and a half degrees. The angle could have been more than 30 degrees without threatening to tip the vehicle over.

The landing site, about 120 miles southwest of the crater Maskelyne, is on the right side of the moon as seen from earth. The position: Lat. 0.799 degrees N., Long. 23.46 degrees E.

Although Mr. Armstrong is known as a man of few words, his heartbeats told of his excitement upon leading man’s first landing on the moon.

At the time of the descent rocket ignition, his heartbeat rate registered 110 a minute–77 is normal for him–and it shot up to 156 at touchdown.

At the time of the landing, Colonel Collins was riding the command ship Columbia about 65 miles overhead.

Mission control informed the colonel, “Eagle is at Tranquility.

“Yea, I heard the whole thing,” Colonel Collins, the man who went so far but not all the way, replied. “Fantastic.”

When the Apollo astronauts landed on the Sea of Tranquility, the temperature at their touchdown site was about zero degrees Fahrenheit in the sunlight, even colder in the shade.

During a lunar night, which lasts 14 earth days, temperatures plunge as low as 280 degrees below zero. Unlike earth, the moon, having no atmosphere to act as a blanket, is unable to retain any of the day’s warmth during the night.

During the equally long lunar day, temperatures rise as high as 280 degrees. By the time of Eagle’s departure from the moon, with the sun higher in the sky, the temperatures there will have risen to about 90 degrees.

This particular landing site was one of five selected by Apollo project officials after analysis of pictures returned by the five Lunar Orbiter unmanned spacecraft.

All five sites are situated across the lunar equator on the side of the moon always facing earth. Being on the equator reduces the maneuvering for the astronauts to get there. Being on the near side of the moon, of course, makes it possible to communicate with the explorers.