Two weeks ago the Perseids lit up the night sky, delighting astronomy buffs with a fireworks display of meteors.

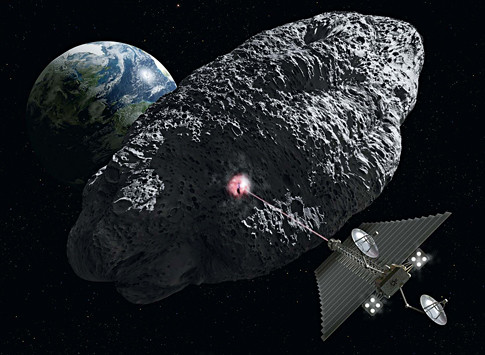

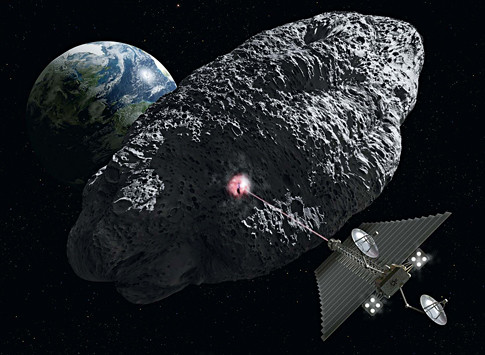

But what would happen if a true grand finale was coming our way in the form of an asteroid that could change life on Earth as we know it?

That’s a question posed in the latest issue of Popular Science.

From the article:

There are between one and two million near-Earth objects (NEOs)—chunks of space rock whose orbits may pass within 30 million miles of Earth—that pose a significant impact threat to the planet. Of the 4,535 NEOs detected and tracked (704 of which are real whoppers), none are on a definite collision course, but there could be millions more, many of them potentially lethal, lurking in the cosmos.

Detection

Who’s Watching? Most spotting is done by half a dozen optical telescopes in the U.S., Italy, Japan and Australia, coordinated by such programs as the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) project, a NASA-funded collaboration between MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory and the U.S. Air Force tasked solely with the detection and cataloging of potential NEOs. Amateur astronomers worldwide also aid the effort. Collectively, the programs discover a new NEO every few days.

What’s the Plan? Since 1998, NASA has funded Spaceguard, a consortium of observatories working to find 90 percent of the half-mile-plus NEOs by 2008; the group has found three quarters of the predicted 1,100 NEOs in this size class. Spaceguard’s next step is to find 90 percent of NEOs measuring 460 feet or larger—potentially up to 12,000 objects—by 2020, but funding has not been secured. Larger wide-field scopes should come online in Hawaii, Arizona and Chile in the next decade, greatly speeding detection.

Our knowledge of asteroids and the early formation of our solar system is likely to increase dramatically in the coming decade, thanks to this fall’s launch of NASA’s Dawn mission:

[T]he Dawn mission will study the asteroid Vesta and dwarf planet Ceres, celestial bodies believed to have accreted early in the history of the solar system. The mission will characterize the early solar system and the processes that dominated its formation…

Vesta is a dry, differentiated object with a surface that shows signs of resurfacing. It resembles the rocky bodies of the inner solar system, including Earth. Ceres, by contrast, has a primitive surface containing water-bearing minerals, and may possess a weak atmosphere. It appears to have many similarities to the large icy moons of the outer solar system.

By studying both these two distinct bodies with the same complement of instruments on the same spacecraft, the Dawn mission hopes to compare the different evolutionary path each took as well as create a picture of the early solar system overall. Data returned from the Dawn spacecraft could provide opportunities for significant breakthroughs in our knowledge of how the solar system formed.

Where’s the best place to watch the Dawn, er, rise? Apparently, Australia:

A team of four personnel from the United States Air Force will visit Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory to monitor the launch …

The US team will arrive at Alice Springs and travel to Tennant Creek where they will establish a small temporary ground station. Tennant Creek was selected as it affords the best view of the crucial booster separation phase of the launch. As part of the same mission a United States Air Force NKC-135 aircraft will be operating out of Perth International Airport from mid-September and flying over northwest Australia. The launch from Cape Canaveral is planned for between 19 September and 15 October depending on weather and atmospheric conditions.

If you’re more interested in dusk, as it were, be sure to check out Popular Science’s excellent slideshow of past asteroid collisions with our home planet.

Last week, we told you about

Last week, we told you about