The most significant real news coming out of last week’s Satellite 2011 show in Washington was the contract between Intelsat and MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates Ltd. (MDA) of Canada to re-fuel orbiting geosynchronous spacecraft. If successful, it has the potential of shifting the economics of satcom services. MDA has the experience and it takes away some of the thunder created by ViviSat earlier this year.

MDA has been pitching this business for years now, and the people managing the spacecraft could not find a way to (1) accept the engineering risk, and (2) see the financial benefits. The scenario was adroitly summarized by Peter de Selding’s piece in Space News…

- Intelsat will select one of its satellites nearing retirement to be moved into a standard graveyard orbit some 200 to 300 kilometers above the geostationary arc 36,000 kilometers over the equator. It is the most used orbital highway for telecommunications satellites.

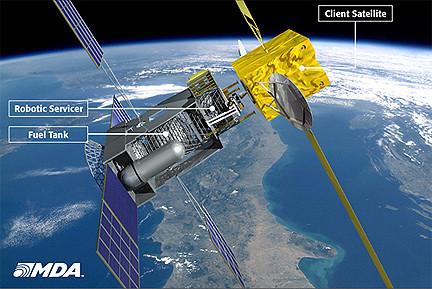

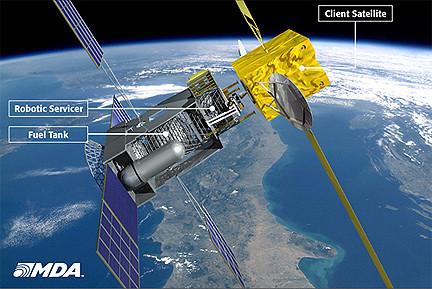

- Richmond, British Columbia-based MDA will launch the SIS servicer, which will rendezvous and dock with the Intelsat satellite, attaching itself to the ring around the satellite’s apogee-boost motor.

- With ground teams governing the movements, the SIS robotic arm will reach through the nozzle of the apogee motor to find and unscrew the satellite’s fuel cap.

The SIS vehicle will reclose the fuel cap after delivering the agreed amount of propellant and then head to its next mission.

MDA Chief Executive Daniel E. Friedmann said in a conference call with investors that MDA has identified more than 40 different types of fueling systems and that the SIS will carry a toolkit designed to open most of them.

Steve Oldham, president of MDA’s newly formed Space Infrastructure Services division, told reporters here March 15 that SIS will be carrying enough tools to open 75 percent of the fueling systems aboard satellites now in geostationary orbit.

Oldham said each mission will last two or three weeks.

So the potential is there for MDA — and you’ve got to give Intelsat credit for looking into the future potential like they’ve got a set. Other operators seem content to wait and see if it works — for now. With 52 orbiting spacecraft, Intelsat is in a good position to give it a go.

Andy Pasztor’s story in the Wall Street Journal latched on to the real financial potential for Intelsat: reselling the service to government customers who have their own spacecraft in need of refueling:

But the seven-year, $280 million contract announced Tuesday is the culmination of MacDonald Dettwiler’s efforts to take the lead in shifting from demonstrations and research to using the technologies in real-world applications.

“This takes it out of the realm of science fiction,” said Kay Sears, president of Intelsat’s government-services unit. “We don’t need to study it any more, we’re going to do it.” Intelsat, based in Luxembourg but with its main office in Washington, operates the largest global commercial-satellite fleet.

By pairing a sophisticated robotic service vehicle with what essentially amounts to an orbiting gas station for satellites, MacDonald Dettwiler intends to shuttle fuel to satellites reaching the end of their normal operational lives of between 10 and roughly 15 years.

Unlike concepts favored by rivals, the Canadian system is designed to have the mobile servicing vehicle disconnect from satellites after they are refueled, a process likely to take several weeks.

According to Ms. Sears, Intelsat chose that approach because it affords maximum flexibility to subsequently move rejuvenated satellites around as market conditions change.

In addition to using the venture to assist Intelsat’s own fleet of more than four dozen satellites, Ms. Sears said the company has the exclusive right to market the first-of-a-kind services to the Pentagon and other prospective U.S. government customers operating satellites, including spy agencies.

Once the venture gains momentum, she said, “it’s going to change the industry” and offer U.S. government officials “a nice opportunity to use a cost-effective” solution to avoid huge replacement costs for certain aging satellites.

This creates a new market in the space business, so I’d expect ViviSat’s simplified solution to gain some traction with other operators in the near future.